How a Social Enterprise Aims to Disrupt The Status Quo of Tea, Trade, and Employment in East Africa

A dozen women in green uniforms gather around a long table. The scent of cardamom, cinnamon, and other tropical spices from the nearby island of Zanzibar fill the air. Nimble hands sort tea leaves and spices, meticulously weighing quantities to ensure the mixing ratio is correct. This is what the production room of Kazi Yetu in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania looks like. Here, high-quality tea blends from the company’s first brand, Tanzania Tea Collection, are produced for the local and international market.

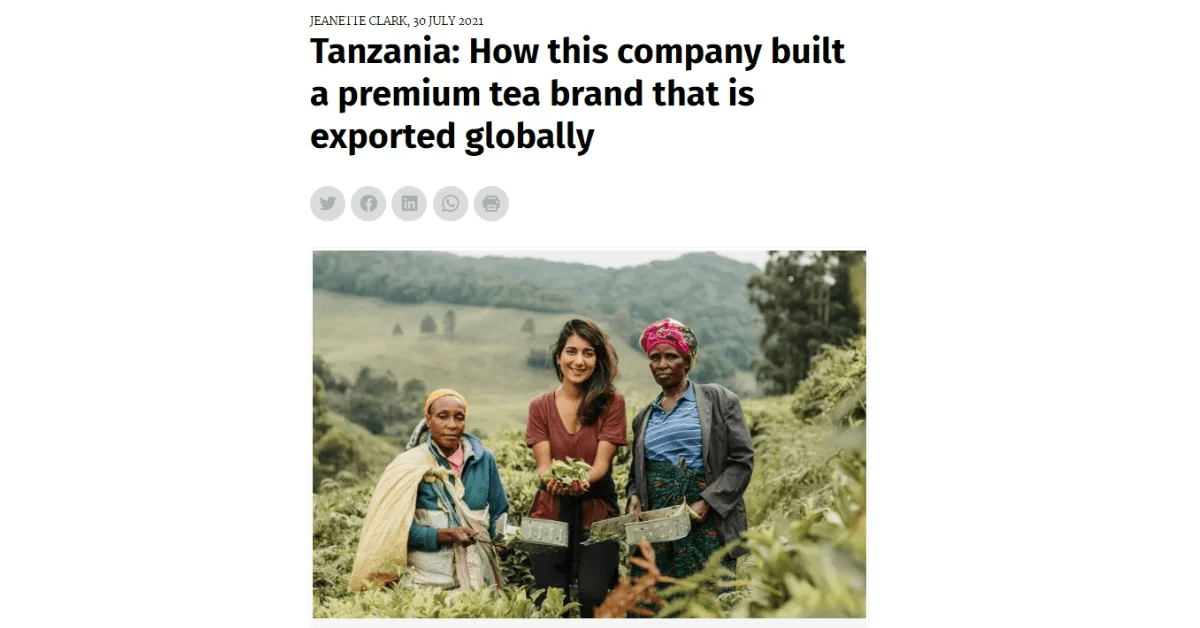

Tahira Nizari and Hendrik Buermann founded the social enterprise in 2018 with the aim of building local value chains in Tanzania and changing how products are produced and traded globally. Both have many years of experience in the field of development cooperation and after their marriage moved to the East African country of Tanzania, where Nizari has family ties. Her ancestors emigrated from India to East Africa around 1900 and her mother grew up in northern Tanzania. Nizari and Buermann named their social enterprise “Kazi Yetu”, which translates to “Our Work” in Swahili, the national language of Tanzania.

“On the one hand we want to improve the income of small farmers by paying premium prices for the ingredients and on the other hand we want to create fairly paid jobs especially for women outside of agriculture through our own tea manufacturing,” says Tahira Nizari, describing the idea for starting the company.

A company for women

Tahira Nizari is all the more proud that Kazi Yetu is playing a pioneering role in Tanzania when it comes to the advancement of women and gender equality. 22 of their current total of 26 employees are female. Above all, she sees the responsibility of companies to proactively bring women into all levels of a company and to specifically promote them. “We promote the leadership qualities of our employees with a special team leader approach. With support, women can gradually develop their skills and increase their self-confidence,” says Tahira Nizari.

Most of the 17 employees in production are single mothers and have to contend with a particularly large number of challenges. At Kazi Yetu, they earn more than twice the minimum wage and have pension and health insurance. In addition, the women can apply for an interest-free loan, which will be repaid over an agreed period.

Although Tanzania has been classified as a lower-middle-income country by the World Bank since June 2021, more than half of the population still lives in poverty. Women are particularly affected, as the Integrated Labor Force Survey 2020/21 shows: Women earn less, are more often employed in precarious jobs and are more often unemployed.

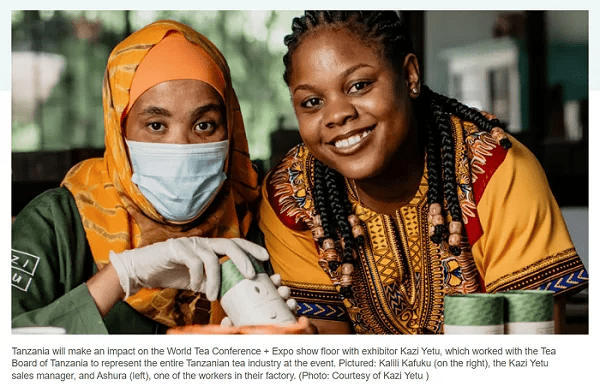

The numbers in the report match the personal experiences of Kazi Yetu employees. A big problem is the unequal payment of women and men, despite the same job and qualifications, says Modesta Kaboyoka, manager there. In addition, women are primarily responsible for the family and household in Tanzania. A woman may not have the opportunity to take on a full-time job because of her family commitments, although she would like to. “Unfortunately, most women aren’t thought of as leaders either,” adds Kalili Kafuku, sales manager at Kazi Yetu. Consequently, it is not surprising that in the past 80 percent of applicants for management positions at Kazi Yetu were men, despite the fact that the social enterprise explicitly encourages women to apply in every job vacancy.

International tea trade

As an export company, Kazi Yetu is also involved in international trade relations and therefore knows first-hand how challenging it is to redistribute economic profits from the Global North to the Global South. The cultivation of the tea leaves happens either on tea plantations or in the fields of small farmers. After the first processing steps, which have to take place within a few hours for freshly harvested tea leaves, most tea is sold as unrefined bulk goods at auctions or directly to dealers. The producers only receive a minimal part of the sum for which the tea is sold.

If a tea plantation is fair trade certified, the producers receive a guaranteed minimum price that is above the market price, a fair trade premium and, in the case of organic certification, an organic premium. “But this is exactly where we want to go one step further, because the Fairtrade system still has a strong focus on agricultural production. Unfortunately, the development of local value chains is not the focus here,” says Tahira Nizari. Promoting local value creation and the associated creation of jobs outside of agriculture makes all the more sense when you look at the unemployment figures in Tanzania. This is higher in cities than in rural regions, and even three times as high among women. 9 percent of women are unemployed in rural areas, compared to 29 percent in Dar es Salaam. So instead of continuing to export agricultural products as raw materials, further processing should be used. Because every additional step in the processing process means more profit on site and can enable the promotion of women.

***This text is the English translation of the article “Kann Tee die Welt verändern?” which got published in the Austrian magazine Frauen*solidarität in June 2022 (frauen*solidarität 2/2022).